The 6 Ds of Brenda Gatlin - Master of the Coaching Dance

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

September 30, 2021

She is remembered fondly as one of the greatest to ever coach in the Detroit Public School League and the State of Michigan, yet you won’t see Brenda Gatlin’s name among the leaders in all-time basketball victories. A search of the MHSAA List of Girls Basketball Champions displays her name only once.

You will, however, find Gatlin’s name in one most unexpected, yet fitting place.

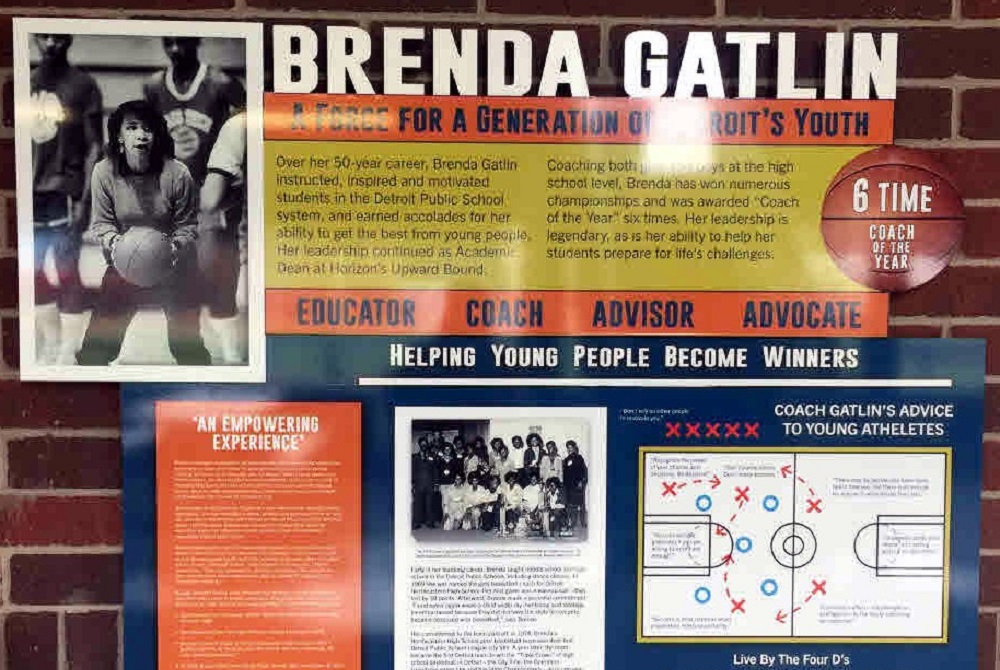

The Corner Ballpark, the redevelopment of the site of historic Tiger Stadium – located at Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood – includes the Hank Greenberg Walk of Heroes. Opened in 2019, the “exhibit features 12 stories of Michigan citizens who displayed character, innovation and trailblazing spirit in the sports field and the community at large.”

The Corner tribute, as one might expect, includes Tigers greats Greenberg, Hank Aguirre, and Willie Horton. Norman ‘Turkey’ Stearns, a baseball Hall of Fame member and legend with the Detroit Stars of the Negro League is another honoree.

Mixed in with the other eight is Gatlin. The honor is most deserved.

Champion in Life

Gatlin never expected to coach basketball.

“I was a dance teacher,” she told The Southeastern Jungaleer, a public forum for the students and community of Southeastern High School published in the Detroit Free Press in 2009 at the time of her retirement after 43 years in public education. “Early in my teaching career I was asked to coach. I knew nothing about basketball.”

The daughter of a gifted clarinetist, who taught at Lincoln University then left for Virginia State College (VSC) where he became the Head of the Music Department, Gatlin was born in Jefferson City, Mo., to Dr. F Nathaniel Gatlin and his bride, Mildred Pettiford Gatlin, an elementary education teacher and reading specialist. The family moved to Petersburg, Va., when her father accepted a position at VSC. Brenda graduated from segregated Peabody High School – the earliest publicly-funded high school for African Americans in Virginia.

“Dad was strict and no nonsense – mom, nurturing and loving,” Gatlin recently recalled of her parents. “Dad was loving also, but his life was filled with so many trials and tribulations. It would take too much time to explain. He graduated from Oberlin Conservative College of Music, Northwestern University (master’s), and Columbia University (doctorate). Mom graduated from Lincoln University (bachelor’s) and VSC (master’s).

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

Brenda began teaching in Detroit at Barbour Middle School in 1966: “I started my tenure with Detroit Public Schools immediately upon graduating.”

“When I came to Detroit, I only planned to stay here three years. But I fell in love with the city,” she told the Free Press in 1976.

Her next career move was to Detroit Northeastern for the 1969-70 school year.

“I went to the Office of Human Resources and they had an opening at Northeastern high school for a Health and Physical Education and Dance Teacher. All of my classes were dance. I was elated. … My love was always Ballet, and Modern Dance,” she said. “At one of our department meetings, Norm Morris, Department Head, said we need a girls’ basketball coach.”

Both programs were long-established athletic department activities with histories that dated back decades at the school, once located on Detroit’s Lower East Side.

“I was in the midst of creating a choreography for the ALL-City Dance Concert that had been scheduled. Mr. Morris knocked me for a loop and said, Ms. Gatlin, you will coach the girls’ basketball team …” she recalled.

“I never in my wildest dreams ever thought that I would have to coach any sports, especially girls basketball.”

Making of a Coach

As a health and physical education major, Gatlin had played some intramurals and learned about sports mechanics, policies and procedures, and rules and regulations while in college.

“I was familiar with the 6-player rule, but the year I started coaching, the rules for girls had changed from 6-on-6 with a roving player to 5-on-5 with unlimited dribbling” she said. “Well needless to say, I choreographed my plays; I knew about movement. I studied the game as much as possible, but my focus was on dance.

“(I)n our first two seasons, we played only five games (each season),” she said to the Free Press, remembering those days when the girls played only against other Detroit city schools.

“The home team (supplied) oranges at half time, and cookies and milk for a social after the game,” she said recently, describing a completely different era. “You can imagine those girls scrapping and running down the court and then having to sit with the opposing team at the end for a social.”

In 2002, she recalled her opening contest as a coach for Lorne Plant at State Champs: “(Our opponent) proceeded to beat us by about 30 points.”

That game was a turning point.

“When we hosted Central high school, under the coaching jurisdiction of Doris Jones, everything changed. … I greeted Coach Jones. Without a greeting, she immediately said, ‘Where is the gym?’ I knew we were in big trouble.

“Sitting there watching my choreographed plays and movements … watching the determination on the faces of my girls – who looked over to me for answers, which I had none, watching my girls continue to fight and battle, even though they were down by 30 points, changed my life and focus. They just didn’t have the skills to compete. I vowed at that moment, ‘no students under my tutelage would be demoralized or embarrassed because they did not, at least, have the skills to compete.’ That game did it, and I owe it all to Coach Doris Jones. I rolled-up my sleeves and got to work.”

Title IX

The advent of Title IX meant things were changing in girls athletics all over the country.

“I remember attending myriad meetings at Wigle Recreation Center with other Detroit female physical education teachers. (At that time, women were the only ones allowed to coach girls in athletics in Michigan). The purpose of the meeting was to discuss whether girls should adopt the same 10 game schedule as the boys,” she said. “Some of the older coaches, and teachers had comments like: ‘This will be too difficult on the female body … studies show that the female uterus will drop if girls are allowed to run up and down the court for any length of time.’ We had to sit and listen to comments such as that. However, we voted that girls should be provided the same opportunities as boys. I suppose Christine Whitehead, Assistant Director of Athletics, provided Dr. Robert Luby (director of the Department of Health, Physical Education, and Safety for Detroit Public Schools from 1962 to 1983) with our sentiments. With Title IX it was a given. Some people still fought it.”

“Subsequent to the fiasco with Central, I had commenced the process of enhancing my knowledge of the rules and skills inherent in the game of basketball defensively and offensively. I discovered (UCLA coach) John Wooden’s books. His books became sort of my ‘Basketball Bibles.’ I became obsessed with the game. I woke up with basketball, went to sleep with basketball.

“And further, the recreation centers were sending us players who had some experience with the game. The Catholic Schools had a feeder program. We did not. So, my hat goes off to Virginia Lawrence and her sister Evalena, Coach Curtis Green, and many others who taught girls at an early age the skills of basketball.”

With the arrival of the federal law, the MHSAA sponsored its first girls basketball tournament in the fall of 1973. Gatlin’s Falconettes were ready.

Led by Hazel Gibson and the talented Williams sisters (Annette, Helen, and Shelia), they were now among the top teams in Detroit.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

In 1974, Northeastern trounced Murray-Wright, 73-27, winning its first Public School League (PSL) regular-season tournament before 500 fans at Wayne State University’s Matthaei Building. Gatlin’s team again ran into Dominican in the MHSAA Tournament, this time in a District Final. The Williams sisters combined for 61 of the Falconettes’ 71 points but fell 74-71 in a foul-filled game.

The defeat was Northeastern’s only loss in 16 games. Senior Lynn Chadwick posted a career-high 28 points to lead Dominican, which would repeat as Class A champ.

“Girls will play their heart out for you,” Gatlin told the Free Press following the season, “if they believe in you and if you treat them fairly.”

Postseason reward came in 1975 when Northeastern topped Dominican in the MHSAA Semifinals, 75-69, then defeated Farmington Our Lady of Mercy, 67-62, to earn the Class A title. Helen Williams scored 31 in the championship game, while Shelia added 20.

“Everybody knows about Shelia and Helen,” Gatlin told the press, “but it was the defense we got from our guards that did the job for us in the second half. We switched from a zone defense to our press and that made the difference.” Northeastern ended the year with a perfect 20-0 record.

Gatlin spent two more seasons at Northeastern before moving on to newly-opened Detroit Renaissance in the fall of 1978.

College Calls

“In 1978, I was asked to teach in a new examination high school,” continued Gatlin, “Renaissance High School (located at Old Catholic Central School). I hesitated because transferring to Renaissance meant no coaching, for Renaissance would not have an athletic program. It would be strictly academic. I enjoyed the fact that I was a part of the planning process in developing plans for the opening of a new school. The whole Renaissance situation was controversial, because many thought Cass (Tech) was enough. The rest is history. Our students were only able to participate in an intramural program, and I taught dance.”

There, she received a call from the athletic director at University of Michigan-Dearborn. Roy Allen, the associate director of health and education for the Detroit Public Schools, had passed on her name as a possible candidate to lead Michigan-Dearborn’s girls basketball team.

“I was able to juggle my teaching responsibilities at Renaissance with my coaching responsibilities at Michigan-Dearborn,” she said. But balancing the coaching duties would become more challenging as time moved on.

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

Return to the PSL

“In 1981, Dr. Remus, the first principal of Renaissance who convinced me to transfer from Northeastern, was asked to become the principal of Cass Tech. Cass was experiencing some issues that they felt Dr. Remus could clear up,” Gatlin said. “Shirley Burke, the successful girls basketball coach at Cass, was stepping down. Cass also needed a dance teacher. Therefore, Dr. Remus said, ‘Ms. Gatlin, I need you at Cass.’ I think I was ready to get back to the high school level. I learned so much more coaching on the collegiate level and had grown extensively. Coach Burke left me with great players.”

When a teacher’s strike in the fall of 1982 threatened the Lady Technicians’ basketball season, Gatlin and her players petitioned Detroit school superintendent Dr. Arthur Jefferson for equal treatment that was afforded the Detroit PSL prep football teams.

“Coaching staffs at Detroit’s 21 high schools have volunteered to continue the football program after hours despite a three-week-old strike,” wrote Joyce Walker-Tyson in the Free Press. “Schools must play a certain number of games to be eligible for tournaments. While there is no similar requirement for girls’ basketball, Title IX … calls for equality in boys’ and girls’ athletics.

“During the teachers’ strike, (the girls were) the ones who went down to talk to the board (of education) all by themselves,” Gatlin told the Free Press’s Mick McCabe

When all 21 of the girls high school coaches volunteered their services, the girls season was saved, although it started late.

Her 1982 team upset No. 2-ranked Trenton in the Regional Final before advancing to the Class A Quarterfinals and falling to Farmington Mercy 38-34 in a thriller.

The season marked the first of three straight PSL championships won by Gatlin’s teams. At Cass Tech she developed a number of all-city and all-state players, including Pamela Dubose (Iowa/Wayne State), Kendra McDonald (Western Michigan), Nikita Lowry (Ohio State), Adrianne Smiley (Ball State), Clarissa Merritt (Ferris State), Sonya Watkins (Houston) – whose father Tommy had been a running back for the Detroit Lions from 1962-67 – Wendy Mingo, Savarior Moss, Yvette Walters, and others.

Expanded Responsibilities, Greater Influence

In the fall of the 1984-85 school year, Gatlin was asked to also coach Cass Tech’s boys team.

“I looked at my staff and hired the best possible person,” said Jeannette Wheatley, Detroit Cass Tech principal in September 1984. “Brenda is an excellent teacher, and she is a marvelous motivator.”

“I see it as a challenge for all female coaches,” Gatlin said to McCabe after the announcement. “But the men have been doing a dual role for years. The Xs and Os are Xs and Os. Basketball is basketball. Outside the strength factor, it’s the same game.”

Gatlin at Cass Tech, Kathy Curtis at Colon, and Carol Brooks at Burr Oak were all in charge of boys varsity teams that winter. They are believed to be the first to do so in Michigan.

She took the job for a year, but delayed her start. The beginning of the boys schedule in 1984 overlapped the girls postseason. (Prior to the 2007-08 school year, girls basketball was played in the fall in Michigan.) Gatlin didn’t want to shortchange her girls.

The Lady Technicians finished with 22 wins against 4 losses that season, advancing to the Class A Semifinals before falling to eventual champion Flint Northwestern. So it was mid-December before she returned to the boys team for the fourth game of the season, a 60-58 win. A young team, Cass Tech finished 10-9 on the year.

Back in 1974, Gatlin told Hal Schram of the Free Press that she wasn’t sure she wanted to spend the rest of her life coaching basketball.

“You have to be a psychologist, a coach and a sociologist to get the complete job done,” she said.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

In 1992, she moved back to Cass Tech, now as an assistant principal. She became principal at Southeastern in 1999, where she stayed until her retirement.

Determination

Today, she continues to practice her belief in the potential of the human being, working with Cranbrook schools and their Horizons-Upward Bound Program as academic dean. There, she helps students from the Detroit metropolitan area who have limited opportunities to enter and succeed in college.

Her life has always been built around four Ds.

“I still use it even with my students in the Cranbrook Horizons-Upward Bound Program,” she said. “When I use the Ds with Basketball, it becomes five Ds: Determination, Dedication, Desire, Discipline, and Defense.

“My players knew that defense wins games; it’s the name of the game. Offense is for the spectators. Defense is for the win. Our chant in our huddle always ended with, ‘The name of the game?’ They would respond with ‘Defense!’ This would be recited several times in the huddle prior to them taking the floor. My players knew that the most important ‘D’ other than defense is discipline.

“... I may have adopted it from my dad. I also used his quote, ‘The difference between resting on the bench and rusting on the bench is u.’ There were a few others.

“You can be dedicated, you can have the determination and the desire, but if you don’t have the discipline, success may not happen.”

The Sixth ‘D’ - Drive

“I get my determination and drive from my dad. My mom was very mild mannered. They were an awesome couple and a great parental balance for my brother Nat and me,” she said, and that drive – the need to teach – remains strong.

“I can’t stop.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

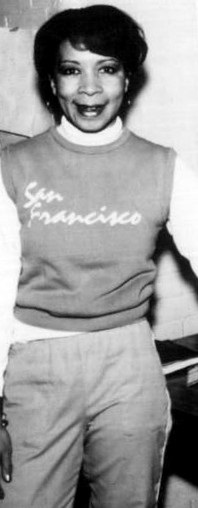

PHOTOS (Top) Brenda Gatlin is among honorees at Detroit’s “Walk of Heroes” display. (2) Gatlin’s first high school position was at Detroit Northeastern, here in 1971. (3) The 1974 Falconettes pose with their first Public School League trophy. (4) Gatlin huddles with the team in 1976. (5) The 1983 Cass Tech team: (Kneeling, left to right) Kim Justice, Ursula Gordon, Andrea Shaw and LaTrece Owens. (Standing, left to right) Coach Brenda Gatlin, Adrienne Smiley, Clarissa Merritt, Wendy Mingo, Kendra McDonald, Nikita Lowry, Kim Wells and Kathy Scates. (6) Gatlin left Cass Tech in 1986 to become athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch from multiple school yearbooks.)

Retired Official Gives Alpena AD New Life with Donated Kidney - 'Something I Had to Do'

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

May 3, 2024

TAWAS CITY – Jon Studley woke up Feb. 20 with a lot of fond memories on his mind, which turned into a collection of 47 photos posted to Facebook showing how he’d lived a fuller life over the past year with Dan Godwin’s kidney helping power his body.

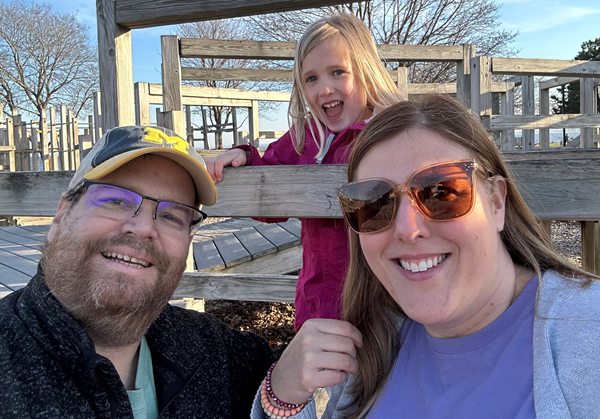

There was Studley at the beach, taking a sunset shot with wife Shannon and their 5-year-old daughter Maizy. In others Dad and daughter are at the ice rink, making breakfast and hitting pitches in the yard. Studley made it to Ford Field to cheer on the Lions, supported his Alpena High athletes at MHSAA Finals and traveled to Orlando for a national athletic directors conference.

Their faces are beaming, a far cry from much of 2021 and 2022 and the first few months of 2023 as the Studleys and Godwins built up to a weekend in Cleveland that recharged Jon’s body and at least extended his life, if not saved it altogether.

“People that saw me before transplant, they thought I was dying,” Studley recalled Feb. 21 as he and Godwin met to retell their story over a long lunch in Tawas. “That’s how bad I looked.

“(I’m) thankful that Dan was willing to do this. Because if he didn’t, I don’t know what would’ve happened.”

By his own admission, Studley will never be able to thank Godwin enough for making all of this possible. But more on that later.

Studley and Godwin – a retired probation officer and high school sports official – hope their transplant journey together over the last 23 months inspires someone to consider becoming a donor as well.

For Studley, the motivation is obvious. Amid two years of nightly 10-hour dialysis cycles, and the final six months with his quality of life dipping significantly, Studley knew a kidney transplant would be the only way he’d be able to reclaim an active lifestyle. And it’s worked, perhaps better than either he or Godwin imagined was possible.

For Godwin, the reasons are a little different – and admittedly a bit unanticipated. He’d known Studley mostly from refereeing basketball games where Studley had served as an athletic director. He’d always appreciated how Studley took care of him and his crew when they worked at his school. But while that was pretty much the extent of their previous relationship, some details of Studley’s story and similarities to his own really struck Godwin – and led him to make their lifelong connection.

“It’s been rewarding for me. I have told Jon, and I’ve said this to anyone who would listen, that I’m grateful and feel lucky that I’ve been part of this process,” Godwin said. “I don’t feel burdened. I don’t feel anything except a sense of appreciation to Jon that he took me on this journey. I didn’t expect that, but that’s how I feel.”

Making a connection

As of March, there were 103,223 people nationwide on the national organ transplant waiting list, with 89,101 – or more than 86 percent – hoping for a kidney, according to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). More than 46,000 transplants were performed in 2023, including the sharing of more than 27,000 kidneys.

Godwin giving one to Studley was among them.

Studley, 43, has served in school athletics for most of the last two decades since graduating with his bachelor’s degree from Central Michigan University. After previously serving as an assistant at Mount Pleasant Sacred Heart, he became the school’s athletic director at 2009. He moved to Caro in 2012, then to his alma mater Tawas in 2015 for a year before going to Ogemaw Heights. He then took over the Alpena athletic department at the start of the 2020-21 school year, during perhaps the most complicated time in Michigan school sports history as just months earlier the MHSAA was forced to cancel the 2020 spring season because of COVID-19.

He's respected and appreciated both locally and statewide, and was named his region’s Athletic Director of the Year for 2019-20 by the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Association. Concurrently with serving at Sacred Heart and earning his master’s at CMU, Studley served as athletic director of Mid Michigan College as that school brought back athletics in 2010 for the first time in three decades. He also served four years on the Tawas City Council during his time at Tawas High and Ogemaw Heights.

Toward the end of his senior year of high school in 2001, Studley was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. For the next two decades, he managed his diabetes primarily with insulin and other medication. But during that first year at Alpena, his health began to take a turn. Studley had been diagnosed with a heart condition – non-compaction cardiomyopathy – which led him to Cleveland Clinic for testing. A urine test in Cleveland indicated his kidneys might not be working like they should – which led to a trip to a specialist and eventually the diagnosis of kidney failure and the start of dialysis, with a kidney transplant inevitable.

Toward the end of his senior year of high school in 2001, Studley was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. For the next two decades, he managed his diabetes primarily with insulin and other medication. But during that first year at Alpena, his health began to take a turn. Studley had been diagnosed with a heart condition – non-compaction cardiomyopathy – which led him to Cleveland Clinic for testing. A urine test in Cleveland indicated his kidneys might not be working like they should – which led to a trip to a specialist and eventually the diagnosis of kidney failure and the start of dialysis, with a kidney transplant inevitable.

Dialysis long has been a standard treatment for people with kidney issues. But it can take a toll. In Studley’s case, that meant being tired all the time – to the point of falling asleep at his desk or having to pull over while driving. He wasn’t receiving enough nutrients and was unable to lift things because of the port for the dialysis tube. Extra fluid building up that his body wouldn’t flush made him constantly uncomfortable.

The next step was transplant, and in July 2021 he was approved to receive a kidney.

The Studleys thought they had a prospect early on, as an aunt on Shannon’s side was a candidate for a paired match – her blood and tissue types weren’t a match for Studley, but matched another person on the waiting list whose donor would be a candidate to give Studley a kidney. But that didn’t work out.

Others showed interest and asked about the process, especially after Studley’s 20-year class reunion in 2021, but nothing concrete came about. Amid the early disappointment, Studley took some time to consider his next move – and then put out a plea over Facebook that fall to his close to 1,000 connections hoping that someone, anyone, might consider.

“I took a week to really think about it – this is what I’m asking for someone to do. I had to get over it in my mind that it was OK to ask,” Studley said. “I’m going to ask someone to make a sacrifice for me, and that’s not me. I always want to help everybody else.”

Godwin is that way too. And immediately after reading Studley’s post, he knew he needed to consider making a call.

Strong match

Godwin had moved to Tawas City from Midland in 2014, and after a few years off from officiating decided to get back on the court that following winter.

He thinks he and Studley may have crossed paths at some point during Studley’s tenures at Sacred Heart and Caro, but it was at Tawas where they got to know each other. Although Studley stayed at Tawas just one school year, Godwin continued officiating for him at Ogemaw Heights – and in fact, Godwin’s final game in 2018 was there, during the District basketball tournament. That night, during the first quarter, Godwin tore the plantar fasciitis in his left foot. He didn’t know if he’d be able to finish the game – the officials from the first game that night stuck around to step in just in case – but thanks in part to Studley connecting Godwin with the Alpena trainer during halftime, he was able to get through the final two quarters and finish his officiating career on his feet.

They’d become Facebook “friends” at some point, so Godwin had seen Studley’s posts over the years with Shannon and Maizy. And when he saw Studley ask for help, something hit him – “immediately.”

“I have a 5-year-old granddaughter, almost exactly the same age as Jon’s, and I’m the dad of one child, a daughter, so there were those connections,” Godwin said. “It almost didn’t feel like there was a choice. It felt like it was something I had to do.”

“I have a 5-year-old granddaughter, almost exactly the same age as Jon’s, and I’m the dad of one child, a daughter, so there were those connections,” Godwin said. “It almost didn’t feel like there was a choice. It felt like it was something I had to do.”

Godwin is 66 and always has been in good health. He’s also always been an organ donor on his driver's license and given blood, things like that. But he had never considered sharing an organ as a living donor until reading Studley’s post.

He read it again to his wife Laurie. They talked it over. He explained why he felt strongly about donating, even to someone he didn’t know that well. After some expected initial fears, Laurie was in. Their daughter had the same fears – What about the slight chance something could go wrong? – but told Laurie she knew neither of them would be able to change her dad’s mind.

“It took me a while to get on board with it, even though I knew in the vast majority of cases somebody who donates an organ is going to be absolutely fine. It’s still major surgery,” Laurie said. “I guess he was just feeling so much like it was something he wanted to do, and he is a very healthy physically fit person. So I felt the odds were really good that he was going to be fine.

“And really, probably, the deciding factor was Maizy. We have a granddaughter the same age, so we were just thinking she needs a dad.”

After a few more days of contemplation, Dan called Cleveland Clinic to find out how to get started.

Then he texted Studley.

“I was nervous saying yes. At first, I didn’t know what to say – I just kept saying, ‘You don’t have to do this, but I appreciate it,’” Studley said. “I never want to have somebody do something for me unless (the situation is dire) … so I told him thank you and I appreciate it, and no pressure.”

Generally, Studley said, the donor and recipient don’t receive information on how the other person is progressing through the process. Godwin, however, kept Studley in the loop, which was a good thing. “But then you’re wondering if it’s going to happen,” Studley said, “if it’s truly a match.”

The initial blood test showed that Godwin wasn’t just a match, but a “strong” match, meaning they share a blood type – the rarest, in fact – and Godwin also didn’t have the worrisome antibodies that could’ve caused his kidney to refuse becoming part of Studley’s body.

That was amazing news. But just the start. “There was so much more we had to go through just to get to surgery day,” Studley said.

Long road ahead

Studley relates the transplant process to a job interview. After meeting with a potential boss, the candidate must wait for an answer – and it could come the next day, or the next week, or months later.

There were several more tests for both to take to make sure the transplant had not only a strong enough chance of being successful, but also wouldn’t be harmful for either of them.

“Right up until the time of the donation, (things) can happen. Like they did blood work on me the Friday before the kidney transplant on Monday, and if that had showed something they were going to send me home,” Godwin said. “So I just kept thinking, is this going to work? It seemed that there were more things that could go wrong than the possibility that it could go right. And that sets everybody up for disappointment – me, because I was invested in doing it, and of course Jon and his family because it was important to them.”

Godwin made a trip to Cleveland Clinic in November – about three months before the surgery. It wasn’t a great visit. His electrocardiogram showed a concern, and a few suspicious skin lesions were an issue because donors must be cancer-free. Almost worse, he couldn’t get in for a follow-up appointment for six weeks.

The wait felt longer knowing not only that there was a possibility for disappointment for Studley, but also the potential something could be unwell with Godwin. But then came good news – at his follow-up, Godwin aced his stress test, alleviating any heart concerns, and the dermatologist said the lesions were basal cell carcinoma and not considered risky to the transplant.

Over the next three months, both Godwin and Studley continued to do whatever they could to keep the transplant on track. To avoid COVID, Godwin and his wife isolated as much as they could, and Studley began wearing a mask frequently at work. Godwin cut out alcohol and coffee and began walking regularly to keep in tip-top shape.

In January 2023, both got the final OK, and the surgery was scheduled for Feb. 20.

But that wasn’t the end of the anxiety.

Studley also had undergone a series of tests and doctor visits, and two days before the transplant he had to get a tooth removed to avoid a possible infection.

Then, on the way from Alpena to Cleveland, Studley’s vehicle hit a deer.

“How is this going to go now?” he recalled thinking. “This is how it started. What’s going to happen now?”

Both arrived in Cleveland safely, eventually. The families stayed apart all weekend, Studley and Godwin communicating briefly by text to check in. There were a few more stop-and-go moments. Godwin’s Friday blood work showed something unfamiliar that ended up harmless. On the day of the surgery, Studley was wheeled to just outside the operating room – and then taken back to his hospital room for another 15 minutes of suspense. Once Studley made it into the operating room, his doctors had to pause during the surgery to tend to an emergency.

But finally, the transplant was complete. And seemingly meant to be. Godwin’s kidney was producing urine for Studley’s body before the surgeons had finished closing him up.

Back on his feet

Studley said he knew he’d be fine once he could start walking the hallways at the hospital; he started doing so the next morning. Later that same day after transplant, on the way back from one of those walks, he saw Godwin for the first time since they’d both arrived in Cleveland. “It was absolutely emotional,” Godwin said.

Godwin went home four days after the surgery. Studley stayed the next month with appointments and labs twice a week. Shannon remained with him the first week, then friends Mike Baldwin and Josh Renkly and Studley’s father Larry took turns as roommates for a week apiece.

For the first three months, including his first two back in Alpena, Studley couldn’t go anywhere except for the trip to Cleveland every other week – which has now turned into every other month with virtual appointments the months in between. Total he missed about six months of work – and thanked especially assistant athletic director and hockey coach Ben Henry for shouldering the load in his absence.

Studley’s checkups are full of more good news. His body is showing no signs of rejecting the kidney. And as long as he keeps his diabetes under control, that shouldn’t affect his new organ either.

Shannon sees the difference while comparing a pair of family trips. The Studleys went to Disney World while Jon was on dialysis, and she said he made it through but got home just “depleted.” This past spring break, the family went to Gatlinburg, Tenn., and Jon had visibly more energy for hiking and other activities. The last six months of dialysis, Jon was sleeping a lot, but this spring he’s helping coach Maizy’s T-ball team and overall is able to spend more quality time with her.

“Most of (Maizy’s) life she’s only known him as sick Dad,” said Shannon, a counselor at Alpena’s Thunder Bay Junior High. “He wasn’t able to do a lot of things with her, and I’ve seen a lot more of that, and I think she notices.”

Jon will be taking anti-rejection medicine and a steroid every 12 hours for the rest of his life, but that and some other little life adjustments are more than worth it. All anyone has to do is look at those 47 photos from the Facebook post to understand why.

Jon will be taking anti-rejection medicine and a steroid every 12 hours for the rest of his life, but that and some other little life adjustments are more than worth it. All anyone has to do is look at those 47 photos from the Facebook post to understand why.

Godwin said he feels better now than he did even before surgery. He does his checkups with Cleveland Clinic over the phone. He also said that if Studley had been found at some point late in the process to be unable to except the kidney, Godwin still would’ve given it to someone else on the waiting list. “I was so invested at that point,” Godwin remembered. “That kidney was going.”

The two families got together for a reunion in August in Tawas, where they had lunch and walked the pier and the Godwins met Maizy for the first time. She doesn’t really get what’s transpired, but definitely notices Dad doesn’t have a tube coming out of his body at night anymore.

And it’s clear the two men value the connection they’ve made through this unlikely set of circumstances.

“His attitude has been inspiring,” Godwin said. “Because you’ve been through the mill (and) I’ve never heard a negative thing, ‘poor me’ or anything. And I think maybe that’s what helps keep you going.”

“You talk to people who know Dan, and they said, ‘That’s Dan. That’s what Dan does,’” Studley said, speaking of Godwin’s gift and then addressing him directly. “The hardest part for me, the biggest struggle … is there’s no way I’m going to ever be able to thank you for this.

“It’s like the post I posted yesterday on Facebook. I posted pictures of everything I had done in the last year, and a lot of it was stuff that I hadn’t done in a long time. My way to thank Dan is just living my life the best I can, enjoying my family. … For me, it’s changed my perspective.”

As lunch finished up, Godwin did have one ask in return – not for one of Studley’s organs, but to be part of a special moment that helped drive him to donate 12 months earlier.

“This isn’t the venue, but I’ve thought about this a lot. I’ve never asked for anything and I don’t want anything,” Godwin said, “but I would like to go to Maizy’s wedding.”

“Yeah, you … yes. Yes,” Studley replied. “You can go to anything you want to go to with my family.”

“I’d like to be there.”

“You will definitely be there.”

“I was at my daughter’s wedding,” Godwin said, noting again that connection between the men’s families, and the importance he felt in Studley being there for Maizy like he’d been there for his child.

“You say that, but there were times I didn’t know if I’d make it to Maizy’s wedding. I might not make it to see her graduate. So …” Studley trailed off, ready to take the next step in his life rejuvenated.

Studley emphasized the continuing need for kidney donors and refers anyone interested in learning more to the National Kidney Registry.

PHOTOS (Top) Alpena athletic director Jon Studley, left, and retired MHSAA game official Dan Godwin take a photo together on the shore of Lake Huron one year after Godwin donated a kidney to Studley. (2) Studley cheers on Alpena athletes during last season’s MHSAA Track & Field Finals at Rockford High School. (3) Godwin and Studley meet for the first time after the transplant, and again six months later. (4) Studley, his wife Shannon and daughter Maizy enjoy a moment after Jon had returned to good health. (Top photo by Geoff Kimmerly; other photos provided by Jon Studley.)